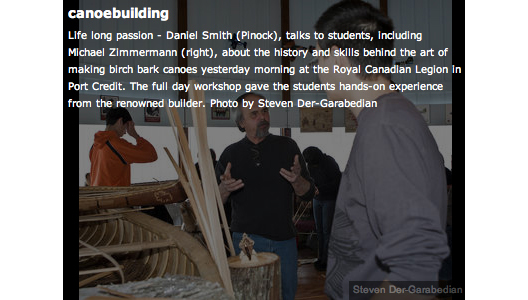

On January 15, 2011, I had the distinct pleasure of spending the day with Pinock Smith, a master builder, known for his traditional canoe-building methods.

I first heard of Pinock in the second season of Ray Mears’ Bushcraft, where he and Ray built an authentic birchbark canoe in a week. They worked on screen again in Northern Wilderness, to build a set of snowshoes. They are both great shows, but nothing can come close to meeting and talking with someone who has that knowledge, and being able to ask the questions that are important to you.

Pinock is an Algonquin, from the Kitigan Zibi First Nations Reserve, in Quebec. A lot of what he does now is teach and use traditional crafting methods — methods that are just as valid and useful today as they were hundreds or thousands of years ago.

A good part of what we spent the day doing was simply learning about properties of building materials, and how to work with them. It’s uncanny how many times this approach is taken by craftsmen that work with raw materials, as I’ve done the same thing working with blacksmiths and bowyers.

By the end of the day, the entire floor was buried under about a foot of cedar shavings. Seems like such a waste, but the place smelled great (He collected it at the end, and I’m assured it was all put to good use).

The tools he used were handmade, and there were so many variations of the crooked knife that he uses for the bulk of his work. I’ve worked with cedar before, but never to this extent, and with this sort of focus. We essentially just sat together and split planks of cedar by hand, thinner and thinner, until they were almost transparent.

As an example of how strong this seemingly papery wood can be, even on a small scale, Pinock took me aside and showed me a tiny sled that he had made — a very detailed model, only about five inches long. There were uprights about the thickness of matchsticks holding up a platform about one inch above the runners, and as I watched in disbelief, he placed it on the floor, and stepped gingerly on it, lifting his other off the ground. With his whole weight fully supported by this tiny model, he continued to talk about its construction, and how he has no need of nails for fasteners, nor paint, varnish, or added oils to finish or protect the wood.

The measured, thoughtful way that he delivered his life experiences was hypnotic, and made it impossible not to pay close attention to the lessons he taught. We focused a great deal on the properties of natural materials, and that dictated techniques, rather than the other way around:

- Birch (the bark is versatile like nothing else),

- Cedar (lots of splitting and re-splitting to get very fine strips to be used for almost anything),

- Ash (very supple and strong),

- Spruce Root (soak in water, split, and dry it. It will last for ages until you need some cordage, when you just re-soak it, and go to work),

- Spruce or Pine Pitch (mixed with bear fat or even Crisco in a pinch, to reduce brittleness, it’s an excellent sealant),

- Rawhide (nature’s self-tightening cable-ties).

Last year, while learning how to carve a bow from a solid stave of hickory, I was taught to use the sound the blade makes through various parts of the wood to reveal a continuous growth ring. I could never have learned that from a book, and the same sort of practical awareness came across in Pinock’s lessons.

The smell of cooking spruce pitch is something to experience, and I now know what consistency is good, and when too much has been cooked off, leaving a grainy, unusable paste. It’s also definitely a two- or three-person job to get it in and through cheesecloth to filter it into pure rosin (especially in the middle of the Canadian winter, when it cools very quickly).

How to keep a split in a root running true, and how to direct its thickness is something you feel by the tips of your middle fingers on each hand, not by looking at it.

Birch bark… don’t even get me started on birch bark.

Many of these techniques and materials weren’t alien to me, but took on a different importance when viewed through Pinock’s eyes. I started seeing the inherent utility and possiblity in everything around me. It’s also nice to know that when you’re hundreds of miles from the nearest hardware store you don’t have to worry, seeing as no rivets, screws, or welds are needed to keep your kit together.

What affected me the most was the sheer love that he has for what he does, and how he lives his life. It’s not one of those burning passions that you can see in someone’s eyes, but a more solid, slow burning dedication to basic concepts and tenets that make up one’s life.

Thanks to Chris and Tim at the Canadian Outdoor Equipment Company for providing the opportunity to spend that time with a wonderful and knowledgeable man, and, of course, to Pinock himself, for an experience I will never forget.

Photos from:

http://www.mississauga.com/community/article/929889–canoe-builders-close-to-nature